- The newly released HIS report by the Department of Statistics Malaysia sheds some light upon the overhang and oversupply issue that is currently plaguing the local property market.

Overhang and oversupply are two very different terms. Simply speaking, overhang (or unsold units) is a cyclical problem due mainly to the unmet housing demand in association with the varying economic performance, housing preferences, market sentiment, credit accessibility and so on. Property oversupply, on the other hand, is a structural problem where the number of houses is in excess of the number of households, as a result of a failure in complying with the housing planning policy, guidelines, and other determinations as contained in the development plans.

To illustrate this: Assuming there are 100 people living in an area, an oversupply happens when the number of houses provided – let say 200 units – which are more than the existing occupiers, leading to the surplus of houses that are not needed in the market. In contrast, the provision of 50 houses is definitely an undersupply but even so, not all these 50 houses can be fully sold out, simply due to the mismatch of price or product that is not in favour of the end-users’ preference. The unsold units, in this case, are termed as overhang.

What is the history of property overhang in Malaysia?

The definition of overhang has been changing over the years. Let’s look at a summary of the various definitions used over time:

- 1999: The total number of housing units remained unsold after it was launched for sale (irrespective of whether the unit is completed, under construction, or not constructed yet)

- 2000-2002: The total number of unsold units for more than 9 months after it was launched for sale (including completed units, under construction and not built)

- 2003 onwards: The total number of completed housing units with Certificate of Completion and Compliance (CCC) and remained unsold for more than 9 months after it was launched for sale.

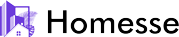

Past experience suggested that the severity of overhang varies with the country’s housing policy and economic performance. During the period of 2004 – 2008, overhangs peaked from 15,558 units to 26,029 units, which is in conjunction with the weak economic performance following the Oil Price Bubble (2003 – 2009) and Global Financial Crisis (2007 – 2009). Since then, overhangs had reduced substantially, from 22,592 units in 2009 to 11,816 units in 2014 (Figure 1), when the market was boosted by easy credit as well as the introduction of the Developer Interest Bearing Scheme (DIBS) to help lower down the buyers’ entry-level.

Again, due to the implementation of various macroprudential and fiscal measures that aimed to curb speculation, the property market had slowed down since 2014, leading to the increase of overhangs that peaked at 32,313 units in 2018.

One can see that overhang always remains there, and to a large extent, its impact to the housing industry relies on the local market condition, which is mainly driven by the favourable lending policy, market optimism from the buyers upon future capital appreciation from property investment, as well as the drumming-up market sentiment from the developers.

While people are unlikely to commit to big and long-term spending right now due to the uncertainties posed by COVID-19, one must recognise that once the vaccine is found or natural immunity is built up, the take-up rate of property will be sure to revive, leading to the reduction of overhang and unsold units in the market. \

How did property oversupply contribute to the overhang issue?

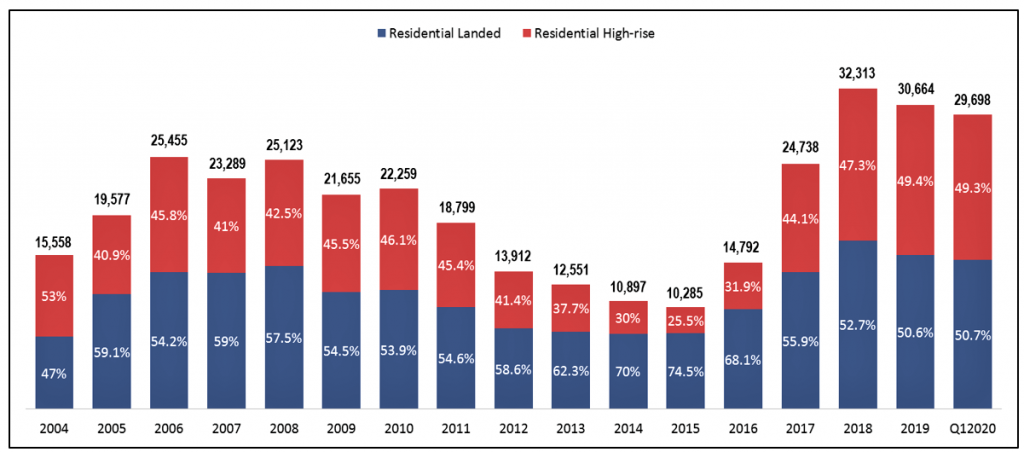

While the problem of residential overhangs seems to lessen after its peak in 2018, the inclusion of commercial-titled residences, such as serviced apartments and SOHO units, has seen to the intensifying property glut in the country. In Q12020, the total number of overhangs, encompassing both residential- and commercial-titled residences, recorded at 48,619 units; where 34.8% of the overhangs were contributed by serviced apartment, followed by residential landed (30.9%), residential high-rise (30.1%), and SOHO (4.1%) (Figure 2).

Residential landed and high-rise properties that used to contribute to the first and second-biggest share of overhangs have been replaced by serviced apartments in recent years. Particularly in states like Johor, Kuala Lumpur and Selangor, serviced apartments accounted for a significant portion of overhangs, which is as high as 67.1%, 45.2%, and 23.2%, respectively.

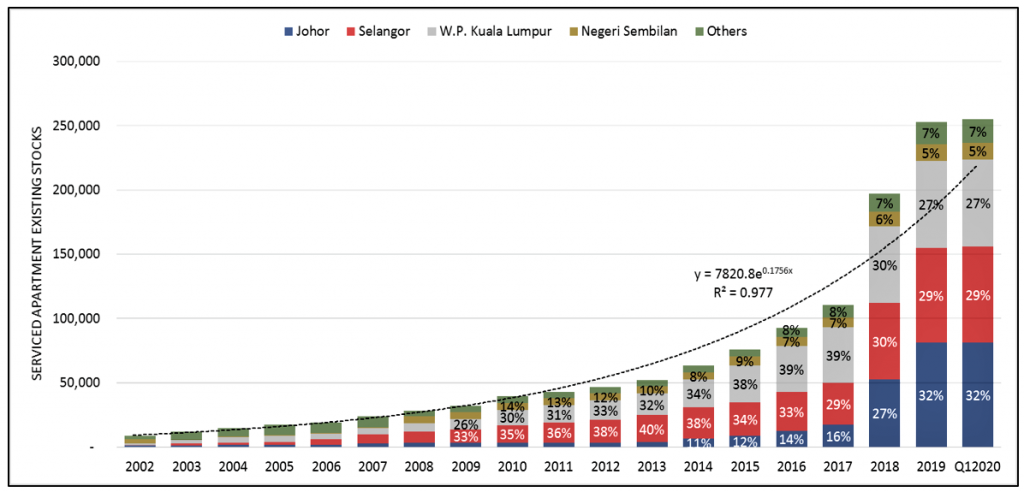

Correspondingly, 88% of the serviced apartment existing stocks in the country were concentrated in these three states – with 32% in Johor, 29% in Selangor, and 27% in Kuala Lumpur (Figure 3). In these areas, a drastic increase of serviced apartments was experienced in 2018, with extensive annual growth of 78.84%, as compared to 2.2% growth of residential landed and 4% growth of residential high-rise properties. This implies that the problem of overhangs we are facing today is neither solely caused by the weak economic performance and market sentiment, nor the desire of property developers to capitalise on high-end products; but to a large extent, the oversupplying of houses that exceed the local market absorptivity.